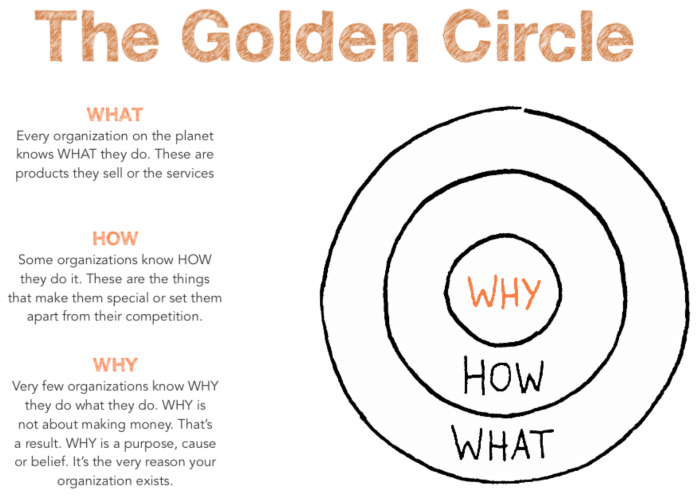

The purpose of education is to create a well-informed, skilled, and collaborative citizenry, capable of creating collective solutions to diverse, multifaceted problems and functioning appropriately in a rapidly evolving global society.

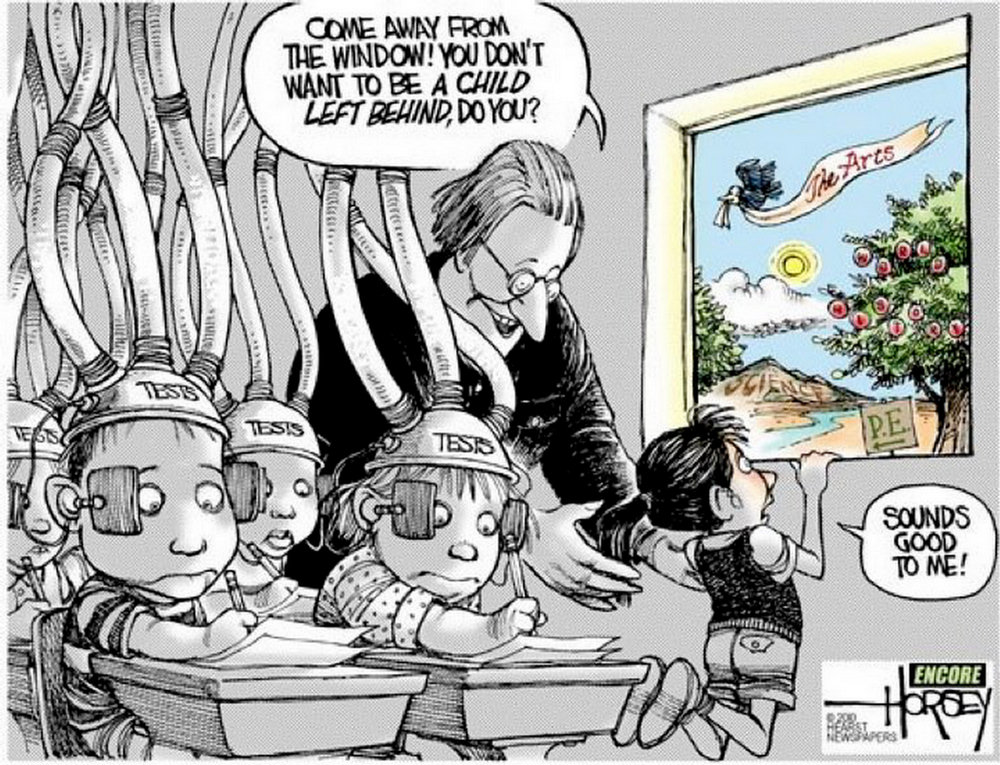

Within this system, student achievements must extend well beyond the learning of specific course content. In today’s technologically advanced and connected society, much of the information we use to teach our students can now be easily accessed online using devices already in their pockets. Instead, today’s students must learn how to filter through this abundance of information, determining which information is accurate, reliable, and valid and which information may be biased, have an alternative agenda, and/or be unreliable. This is no easy task, as much of the information out there today is complexly nuanced and not easily sortable into simple, dichotomous categories.

To establish and maintain a truly differentiated classroom, where learning is assessed based on meeting clear standards, and where students “fail forward” with a growth mindset, a clear priority needs to be placed on building relationships. Being an effective teacher is largely about getting your students to buy into your vision and that isn’t likely to happen if the students do not feel supported and appreciated. Teacher dictators don’t last very long. They get burned trying to convince their students to follow them. While students may comply, they will not be fully committed to the teacher or the teacher’s vision. It will be a constant battle for the teacher to get anything done using such an approach. Therefore, it is essential for teachers to demonstrate a genuine interest in the students they serve. Great teachers look out for and take a genuine interest in the students they serve and place these interests above their own self-interest.

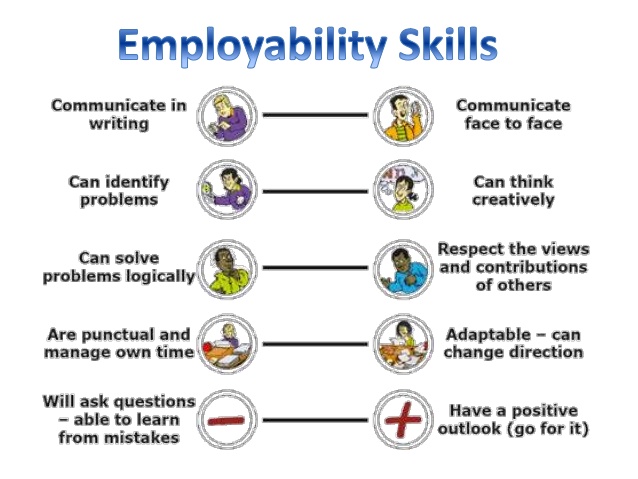

Looking out for our students means we must teach our students how to be critical thinkers and how to skeptically embrace information they read and hear. We as educators must be able to see student learning within a broader context of the skills that are really important for students to be successful in the 21st century. The necessity for this extends beyond the awareness that the world has changed or that the world continues to change. We must also understand that the pace of this change is exponentially increasing at a rate unseen in human history before.

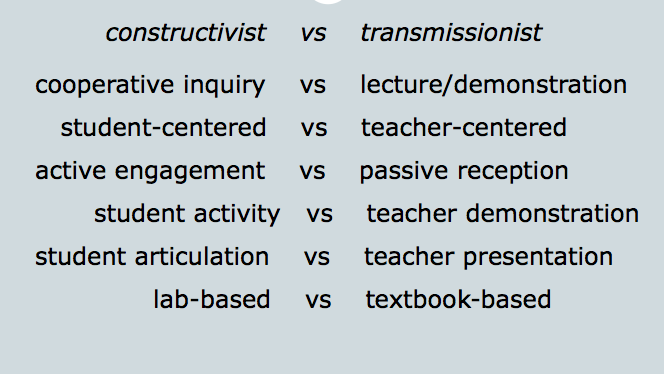

Simply, we must no longer sell our students on a false narrative that only learning course-specific content will be a ticket to their future success in careers that may not currently exist. Rather, we must, to the best of our ability, try to anticipate the methods by which our students will need to apply this information and the skills they will need to be successful. For example, many of my chemistry students will not go on to balance chemical equations and solve stoichiometry problems in their adult careers. I am not suggesting that this content is without importance, but rather that the skills built by learning how to balance chemical equations and solve stoichiometry problems (including: problem solving, critical thinking, attention to detail, collaboration, and communication) are perhaps more important that the specific content being learned as the content merely provides the vehicle to develop those universal skills. However, it is the skills students apply to learn the content that are the true drivers of their educational experience.

Essentially, we want our students to be able to use a variety of problem solving strategies, individually and collectively, to arrive at workable solutions and strategies for addressing progressively difficult, authentic, real-world problems.

In my ecology classes, one of the more challenging projects we have our students complete is to design and maintain a fully self-sustaining ecobottle. In this project, students must research, create, and maintain a balanced ecosystem within their sealed bottle. They must consider the roles and contributions of many abiotic (water, air, soil, etc.) and biotic (microorganisms, plants, animals) factors and how those elements work in harmony with one another to sustain a balanced and healthy ecosystem. The project is challenging as students learn about the many interactions that occur and must be balanced for an ecosystem to function properly.

In addition, our students (and teachers) need to become more comfortable with being uncomfortable, understanding that learning is a messy, non-linear process, where failures are necessary in order to learn from our mistakes, grow and get better. Therefore resilience and a “fail forward” mindset are crucial to our long-term success.

How do we then build this mindset? First and foremost, I believe it starts with rethinking our grading practices. I will honestly admit that I have yet to adopt a fully standards-referenced or standards-based grading system in my classes. I am not exactly sure why this hasn’t happened, as I really believe in the idea and concept of basing a student’s grade around their mastery of a learning target or standard. I am also participating in graduate courses at Drake and have really enjoyed the clarity regarding the learning target and in getting ongoing feedback regarding my level of proficiency around this target or standard.

So while my implementation has lagged behind my philosophy, this is perhaps one area I am most excited about as it relates to making the move to Waukee. Simply stated, here are my beliefs regarding how student learning should be assessed. First, I believe that the purpose of grades is to provide communication to the students and parents regarding the student’s level of understanding and mastery of a specific learning outcome, target, objective, and/or standard. The grade also has a secondary purpose of enabling the student to evaluate their level of understanding on an ongoing basis and make the necessary adjustments, as needed, to improve their level of understanding.

Grades should not be based around minutiae details or simple point accumulation, but rather around big ideas and overarching themes. They should expect students to demonstrate evidence of learning in multiple dimensions and capacities. Therefore, practice assignments, homework, attendance, behavior, and class participation should not be figured into a student’s grade.

In addition, grades are merely snapshots of learning at a given moment in time and teachers must embrace the reality that students learn at different paces; therefore, students should be given multiple opportunities to demonstrate mastery of learning through reassessments. It is also the teacher’s responsibility to provide frequent formative assessment opportunities for students and provide targeted, individualized feedback on these formative assessments in order that students can learn and make adjustments to self-correct and remain on a more focused learning pathway

Also, learning for understanding is an important part of any standards-based grading system. It must no longer be ignored that, over time, students may unlearn a standard. Therefore, students should occasionally be assessed on previously learned content to ensure retention of learning of key concepts and ideas in the course. With reassessments possible, this ongoing practice make learning more permanent.

Formative assessments should be designed for the purposes of providing targeted, diagnostic, task-involving feedback that causes thinking and creates a cognitive shift. Summative assessments should weave multiple ideas and standards together to provide a comprehensive evaluation of learning proficiency.

A grade should make clear what the learning targets are and communicate a student’s progress in demonstrating the ability to meet those learning targets. In summary, a grade represents what a student is able to do at the end of the journey, not the route they took to get there.

In addition, it is important for teachers to respect and recognize each student at unique with unique learning needs. Teachers must identify and prioritize opportunities for differentiation in the classroom. I had the opportunity to learn from Rick Wormeli at the ACSD Curriculum Leadership Academy last week and really took a lot away from his day of talking with us about differentiation.

The first key component to create a truly differentiated classroom is for the teacher to be a reflective practitioner. Differentiation requires the teacher to be flexible and manage ambiguity, to avoid the temptation to standardize and establish equilibrium. Instead, Wormeli argued that we should seek compelling disequilibrium, as learning is episodic and inherently “messy”. He suggests we should embrace the chaos and abandon the “one size fits all” factory model of education.

True differentiation is also largely about cultivating a mindset within students that gives them the strategies they need to advocate for their own learning needs, to be intellectually agile, and to navigate situations that are not already differentiated for them.

To differentiate, I believe teachers must delineate between what is equal and what is fair. In a differentiated classroom, fair isn’t always equal, but rather, and more appropriately, what is appropriate to best meet the learning needs of the individual student. Marzano put it best when he said, “No one knows ahead of time how long it takes for a class to learn anything.”

To accomplish this, teachers should view time as flexible and not immutable, adjusting the pacing of learning and delivery of content into differential “chunks” to accommodate the diverse learning needs of our students. Teachers must know in their lesson plan, what came before, where is the student now, and where they will go next based on where they are now. Teachers must also embrace the reality that 90% of differentiation is about what the teacher does prior to a lesson.

It is important that teachers open their practice up to the scrutiny of others. Steve Barkley says that more lessons need to be filmed and that “Teaching should be examined to at least the same level as blocking in football.” Wormeli suggests that for teachers, it is important to “admit that what they are doing is less effective that their ego thinks it is.” Even if we are doing great work, the reward for hard work is more hard work.

In my work as a Lead Teacher, the learning and teaching in my classroom has become much more public. I have worked a great deal with one of our instructional coaches to come into film many lessons. We then “break down the film” and talk about where the true moments of learning occurred and develop strategies together to leverage and expand upon these moments. This experience has made me a much more reflective practitioner and really improved my efficacy as a teacher over the last two years.

Students also have to embrace the value of differentiation and taking different learning journeys than their peers depending on their learning needs. To get students to buy into this, it is vital for the teacher to prioritize building relationships and a sense mutual respect with and among students. We respect our students by not treating them all interchangeably and taking the time to get to know them, their interests, their preferred learning styles, etc.

~Brad Hurst

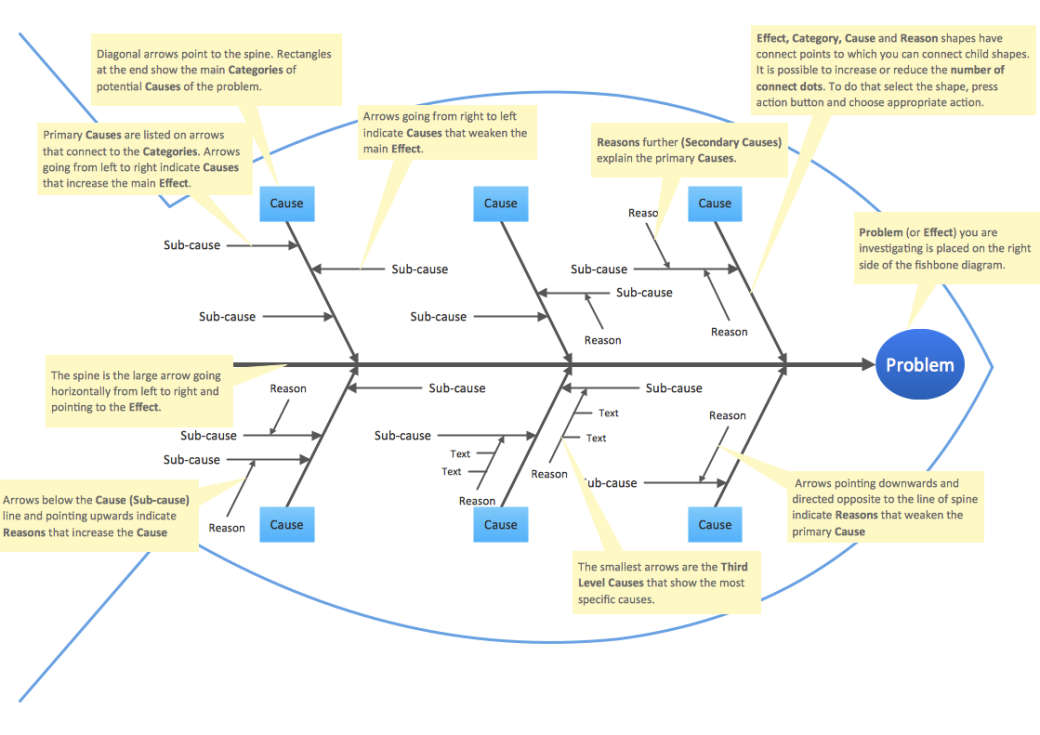

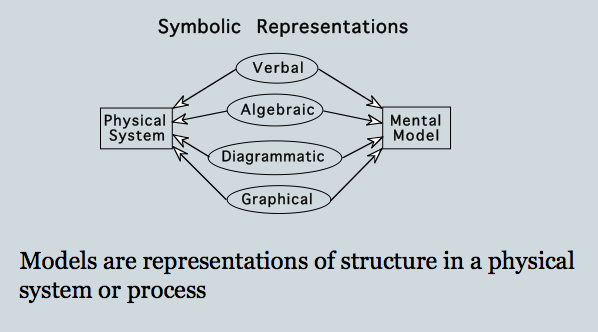

As educational leaders, we must have the self-discipline to see the whole picture, identifying interrelationships and searching for patterns. We must dig deep to identify root causes of problems and challenges, avoiding the temptation to simply react to static snapshots and continually “put out fires.”

As educational leaders, we must have the self-discipline to see the whole picture, identifying interrelationships and searching for patterns. We must dig deep to identify root causes of problems and challenges, avoiding the temptation to simply react to static snapshots and continually “put out fires.”